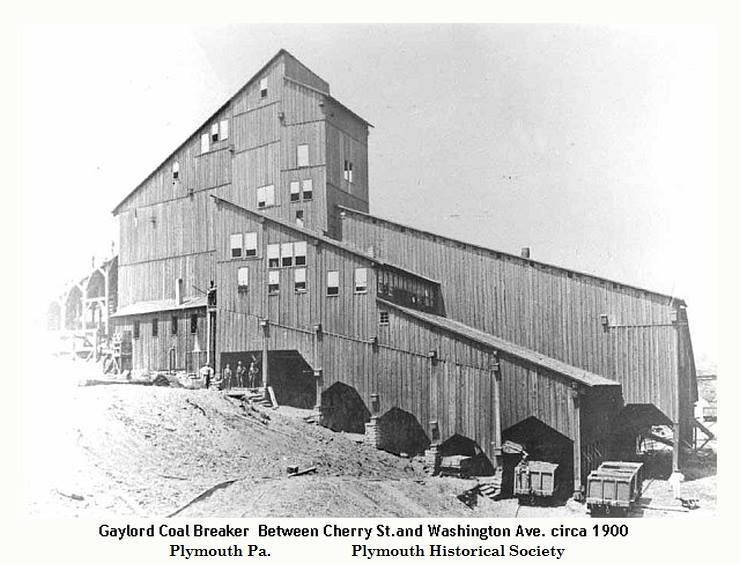

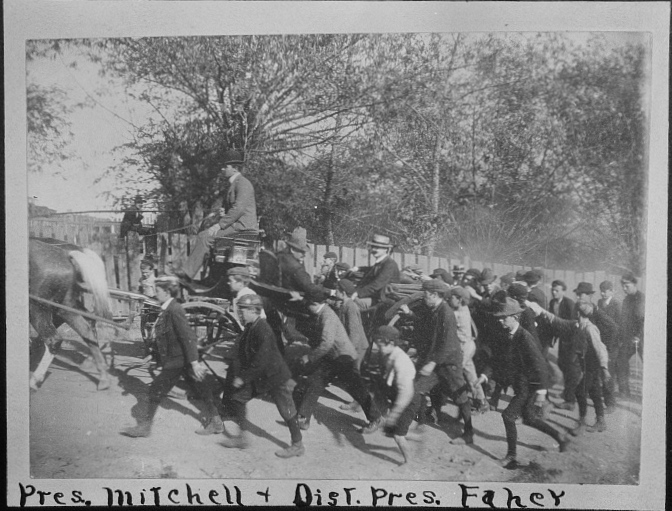

A group of anthracite miners before their work day begins. (Source: http://explorepahistory.com)

A group of anthracite miners before their work day begins. (Source: http://explorepahistory.com)

Schedule of Events, January 2017

Contact Name: Prof. Bob Wolensky, Anthracite Heritage Foundation and King’s College

A regional observance of Mining History Month will take place between January 7-29, 2017, at programs in Wilkes-Barre, Scranton, Pittston, Plymouth, Dallas, Peckville, and Ashley. The annual event focuses on the anthracite industry in Northeastern Pennsylvania, including the mineworkers, their families, and communities.

The programs are sponsored by the Anthracite Heritage Museum, the Anthracite Heritage Foundation, King’s College, Wilkes University, Misericordia University, the Boy Scouts of America-Northeastern Council, the Greater Pittston Historical Society, the Huber Breaker Preservation Society, the Genealogical Research Society of Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Wyoming Seminary Lower School, the Anthracite Café, the Anthracite Living History Group, and the Knox Mine Disaster Memorial Committee.

The public is cordially invited to attend all events (except the first) free of charge.

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS FOR MINING HISTORY MONTH–January 2017

Sat., Jan. 7, 9 am-1 pm Boy Scouts of America: “Mining in Society” Merit Badge Day, Open to Boy Scouts of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Council; (Fourth Floor, Mulligan Science Building, King’s College)

Sun., Jan 8, 7 pm Plymouth Historical Society-Public Program: Presenter: Maxim Furek, “The Sheppton Mine Disaster, August 1963;” Moderator: Steve Kondrad; (Plymouth Borough Municipal Building, 162 West Shawnee Ave.), refreshments

Thurs., Jan 12, 7 pm Wyoming Seminary Lower School-Public Program: Presenters: Clark Switzer and Thomas Supey Jr., “Scratching the Surface: A Chapter in the Anthracite Mining History of Northeastern Pennsylvania;” (Cosgrove Room, Pittston Memorial Library, 47 Broad St., Pittston), refreshments

Tues., Jan. 17, 7 pm Huber Breaker Preservation Society-Public Program: Presenters: Documentary filmmakers John Welsh and Alana Mauger of Philadelphia, “Anthracite Region Mine Fires: Exploring One of the Hidden Costs of Mining;” Discussants: Chris Murley and Banks Ries, The Underground Miners; Moderator: Bill Best; (Ashley Fireman’s Park, 160 Ashley Street, Ashley); refreshments

Thurs., Jan. 19, 7 pm King’s College-Public Program, The Annual Msgr. John J. Curran Presentation: “For the Least of Them,” A one-act play about the life and times of Msgr. Curran, known as “the labor priest” because of his three-decades of work with the anthracite miners, written by Ken Gordon and acted by Billie Herbert; Introduction by Robert Wolensky, King’s College; (Burke Auditorium, McGowan Business School, 133 No. River Street, Wilkes-Barre), refreshments at 6:30 pm

Fri., Jan 20, 7 pm Wilkes University-Public Program: Presenter: Prof. Christine Patterson, Atlanta, Georgia, “African American Coal Miners in Northeastern Pennsylvania: A Personal Perspective;” Discussant: John Hepp, Dept. of History, Wilkes U.; Moderator: Robert Wolensky, Dept. of History, King’s College; (101 Stark Hall, Wilkes U.)

Sat., Jan. 21, 2 pm Anthracite Heritage Museum-Public Program: “The Knox Mine Disaster Commemoration;” Special tribute for William A. Hastie, the last living Knox Coal Company employee; Bill Hastie video tribute by documentary filmmaker David Brocca of Los Angeles, CA; Erika Funke and Frank Tartella will read Knox disaster-related poetry; (at the Museum, 22 Bald Mt. Road, Scranton); refreshments

Sun., Jan. 22, 10 am St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church, Pittston: Annual Knox Mine Disaster Memorial Service,10 am, (35 Williams St., Pittston)

Sun., Jan. 22, 11:30 am Public Commemoration of the Knox Mine Disaster: (PHMC Historical Marker on Main Street, Pittston, in front of Baloga Funeral Home)

Sun., Jan. 22, 12 noon Walk to Knox Mine Disaster Site, weather permitting; (gather at Baloga Funeral Home following the Commemoration)

Wed., Jan. 25, 7 pm Misericordia University-Public Program: “Oral History Projects in Northeastern Pennsylvania: The Importance of Stories;” Presenters: Lucia Daley, Ron Faraday, Melissa Meade, Temple University; Noreen O’Connor, Kings College; F. Charles Petrillo, and Mary Policare; Moderator: Jennifer Black, Dept. of History & Government, Misericordia U.; (McGowan Room of the Bevevino Library), refreshments

Thurs., Jan. 26, 7 pm Genealogical Research Society of Northeastern Pennsylvania & SIAMO-Italian American Heritage Society-Public Program: Presenter: Robert Wolensky, King’s College, “Italian American Mineworkers in the Northern Anthracite Field, 1896-1936;” Moderators: Stephanie Longo and Maureen Gray; (at the Society’s headquarters, 1100 Main Street, Peckville, PA), refreshments

Sat., Jan. 28, 7 pm Greater Pittston Historical Society-Public Program: “Pittston-area Mining Disasters: A Panel Discussion;” Presenters: Ron Faraday, Eagle Shaft (1871); Robert Wolensky, Knight Shaft (1871); Richard Fitzsimmons, Twin Shaft (1896); and Bryan Glahn, Knox (1959); Moderator: Ed Philbin; (St. John the Evangelist Church basement, 35 Williams St., Pittston), refreshments

Sun., Jan 29, 5 pm The Anthracite Café Miner’s Dinner: Special Benefit Dinner on behalf of “The Knox Mine Disaster” documentary directed by David Brocca of Los Angeles, CA; Chef/owner Mike Prushinski will serve an authentic Coal Miner’s Dinner; excerpts from the Knox documentary will be shown; tickets for the evening are $22 are available at https://knoxmine.eventbrite.com or at the Café

A group of anthracite miners before their work day begins. (Source: http://explorepahistory.com)

A group of anthracite miners before their work day begins. (Source: http://explorepahistory.com)