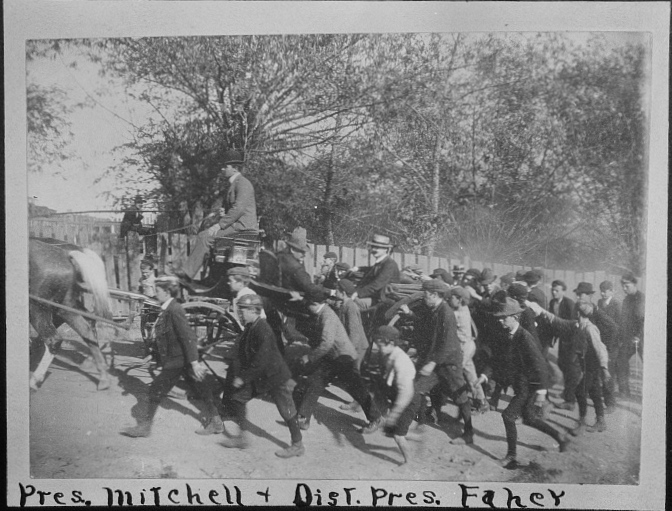

Shenandoah, Pennsylvania. John Mitchell, President of the UMWA (United Mine Workers of America), arriving in the coal town. His open four-horse carriage is surrounded by a crowd of breaker boys. The driver of the high front seat is wearing a derby hat. Credit: Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Background Leading Up to the Coal Strike

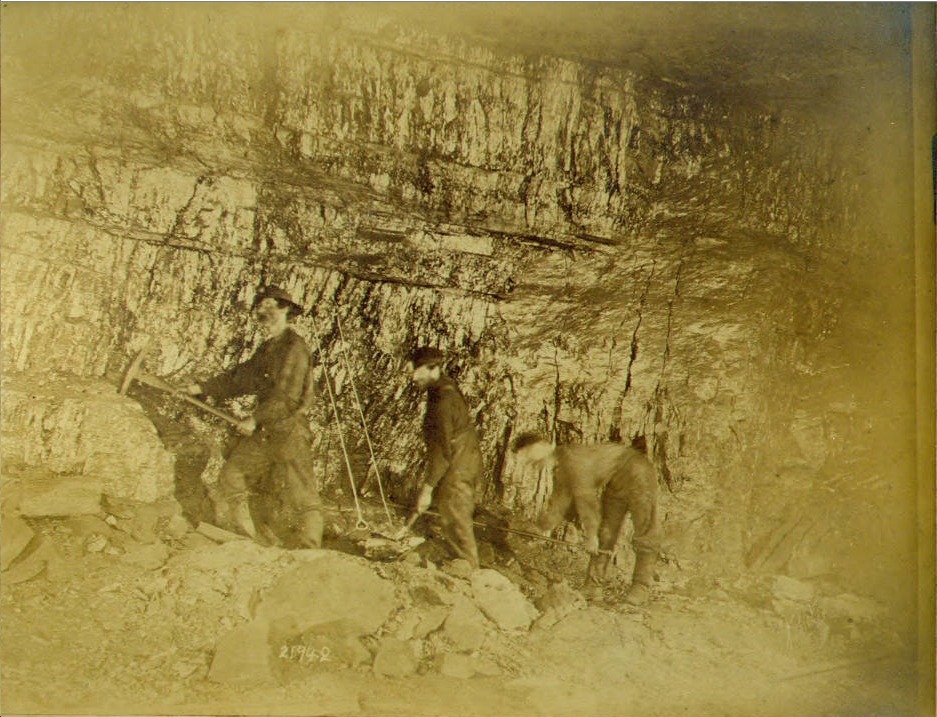

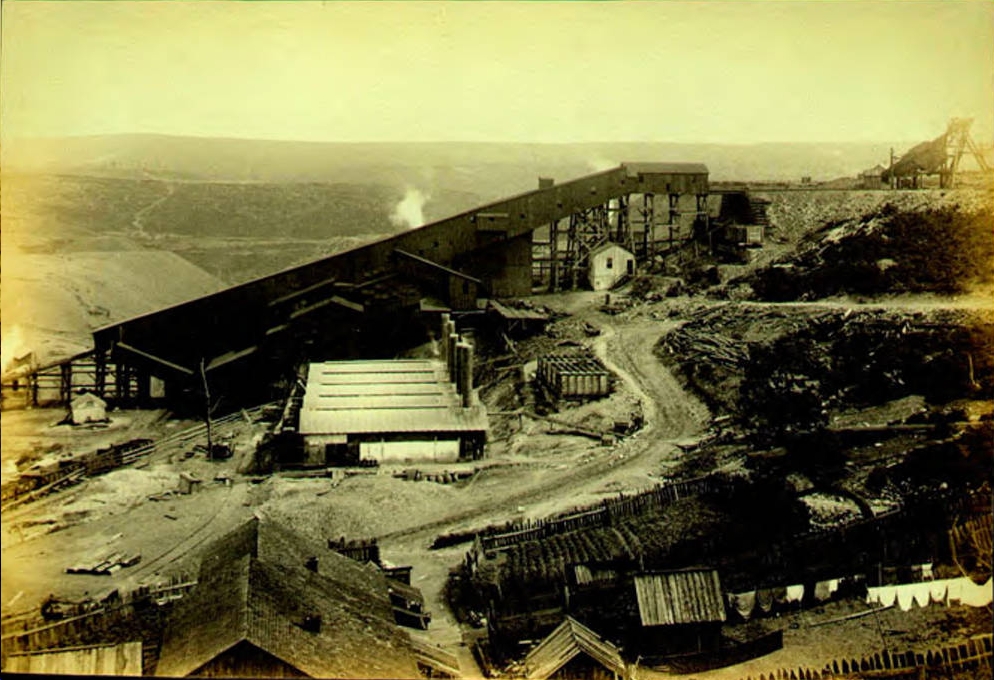

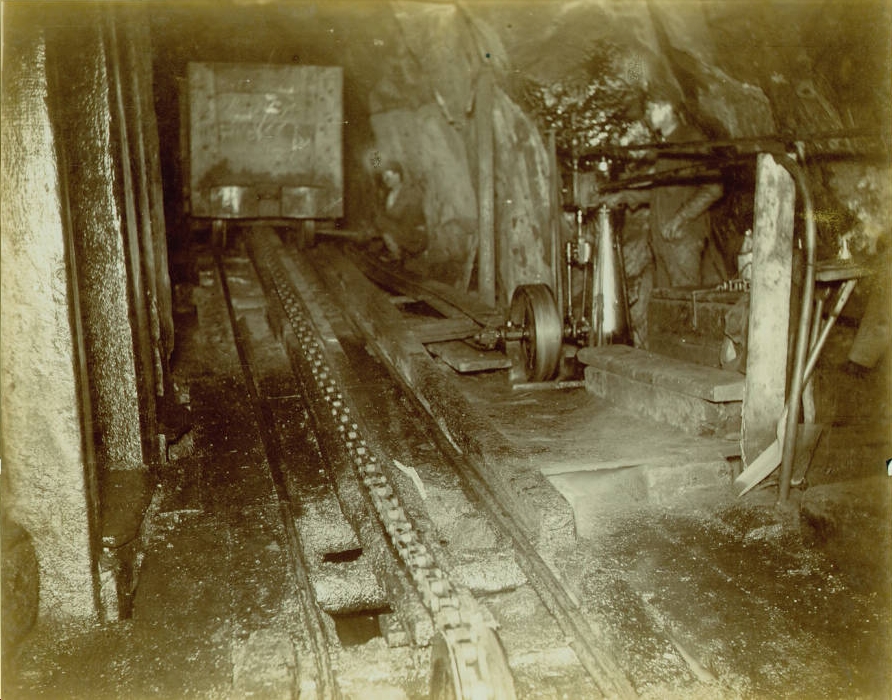

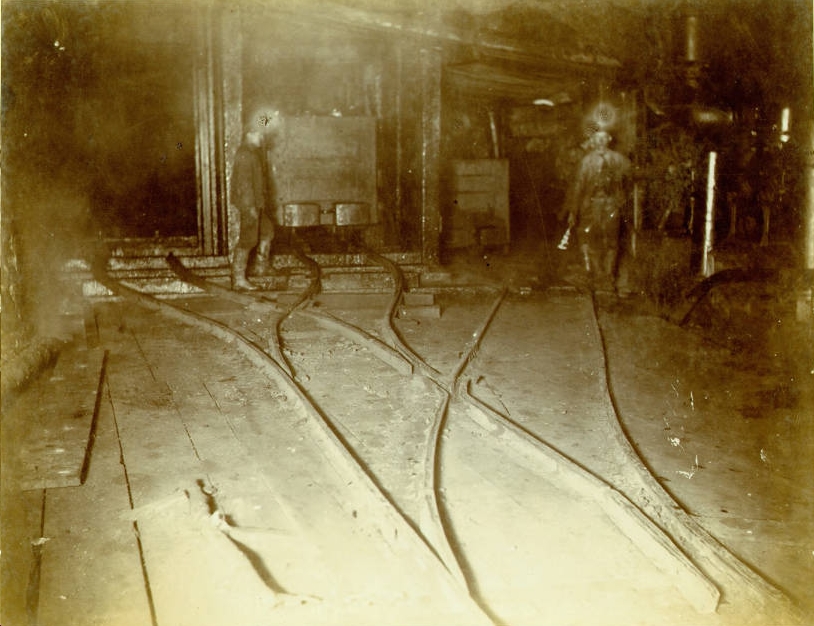

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) became prominent in the late 1890s after a series of immigrant-led protests. One such protest, the 1897 walkout of adolescent mule drivers, culminated in the Lattimer Massacre in September of 1897. Subsequent strikes in 1898 and 1899 asked for the abolition of company stores, the ability to check scales, and recognition of the union. Yet by 1900 the coal operators still refused to speak with the leader of UMWA, John Mitchell. After 100,000 miners walked out for more than a month, coal operators eventually agreed to a wage increase.

The 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike

Reluctant to have another strike and finally able to meet with coal company leadership, Mitchell was not able to negotiate any more of the miners’ initiatives throughout the remainder of 1901. Apprehensively, he agreed to a temporary suspension of work on May 12, 1902. From Mitchell’s letter to Mother Jones, he writes:

“I have every reason to believe that the strike will be made general and permanent. I am of the opinion that this will be the fiercest struggle in which we have yet engaged. It will be a fight to the end, and our organization will either achieve a great triumph or it will be completely annihilated. Personally I am not quite satisfied with the outlook, as the movement for a strike is strongly antagonized by the [union] officers of the lower District, and of course the success of the strike depends entirely upon all working in harmony and unison.” (Quoted from Miller and Sharpless 1985: 256-257)

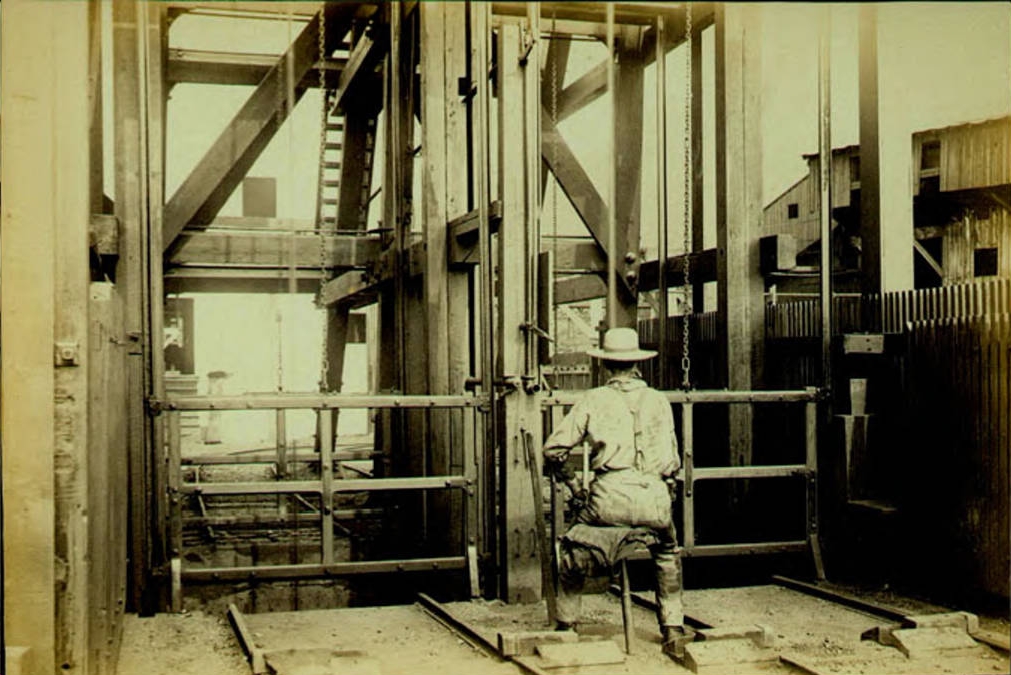

The 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike would last six months wherein miners went on strike for better wages, union recognition, and shorter workdays. The strike had a stark economic effect on the region as 140,000 men and boys were not taking part in the economy. Businesses suffered. Banks did not receive deposits. Local society was divided amongst the majority who were workers and supported the strike and the 5,000 mine bosses and clerks who sided with the coal operators. Single men of Slavic origins headed back to their homelands. Others headed to the bituminous fields. The oldest children left the family to try to offer support by heading to the big cities.

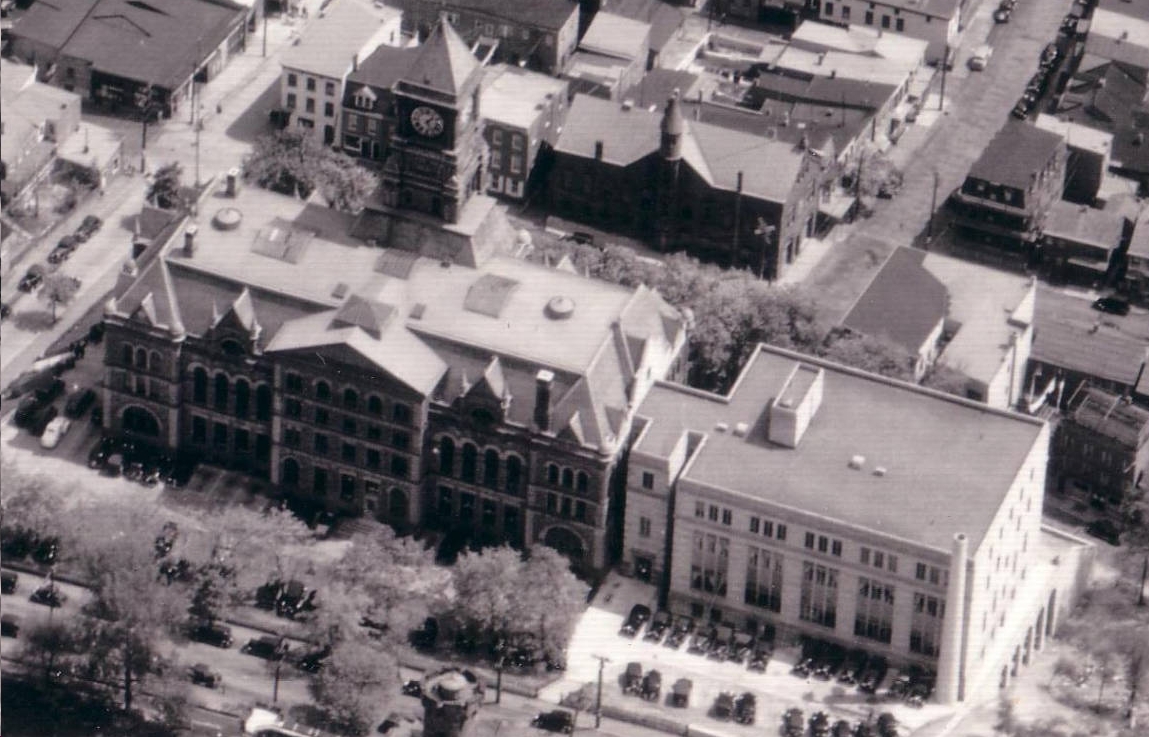

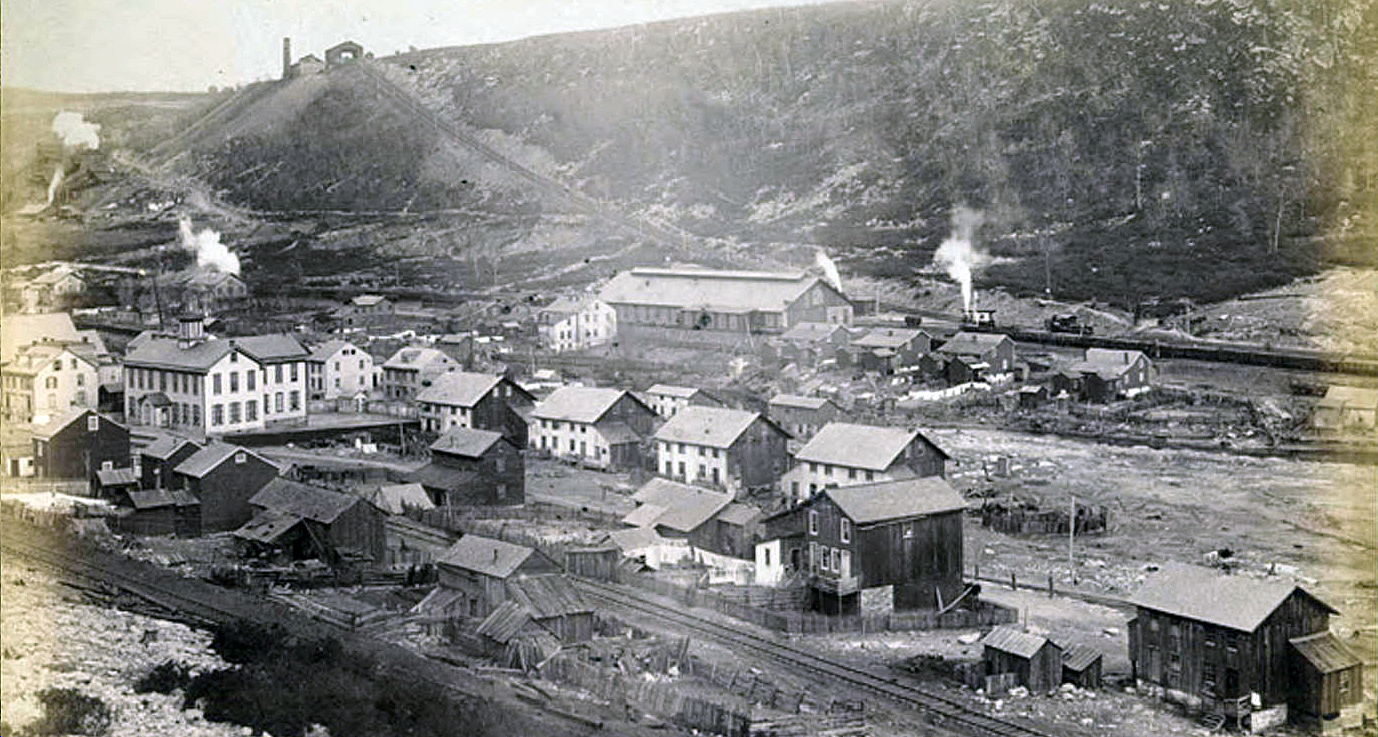

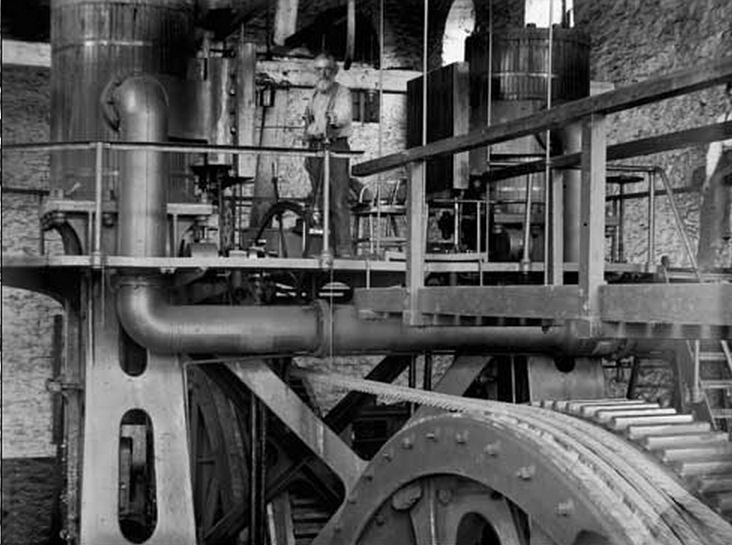

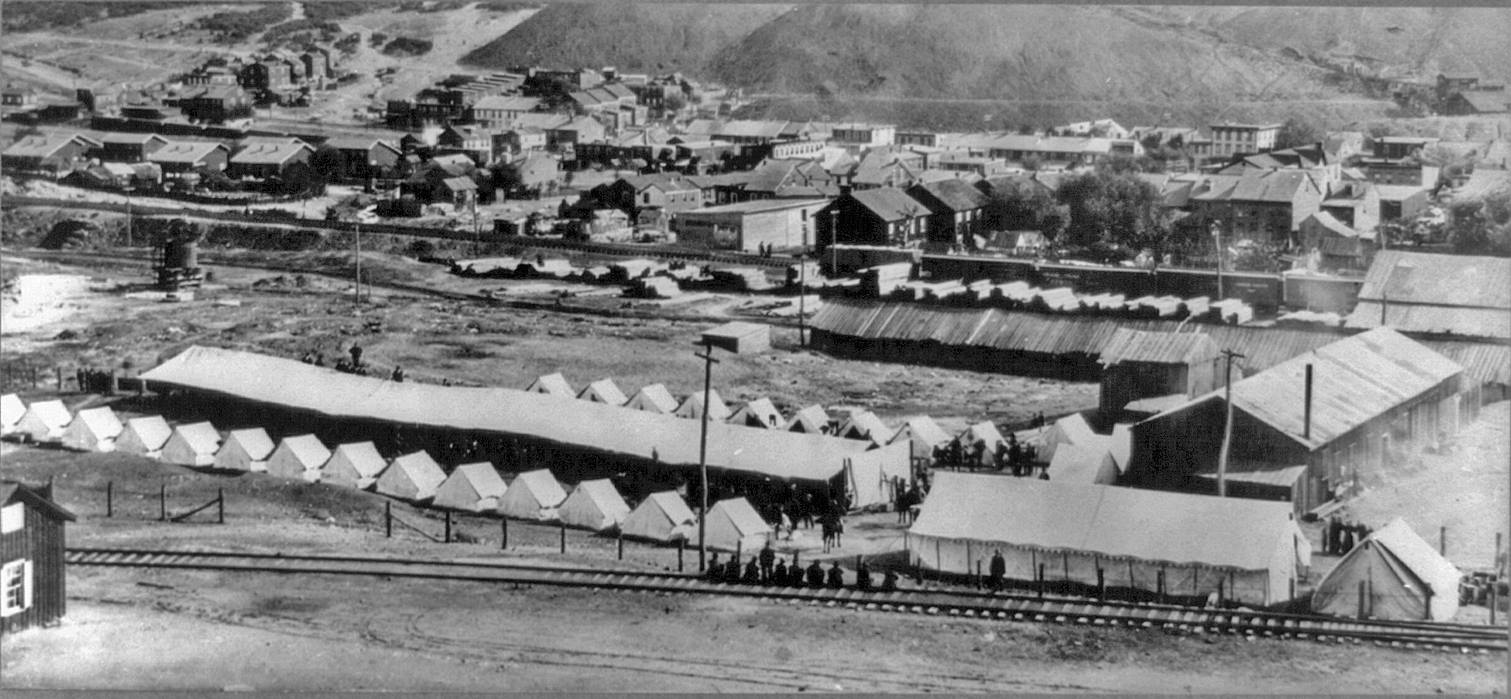

Despite these hardships, journalists who came to anthracite towns to observe the strike were surprised at how peaceful the region was. Mitchell and UMWA officials urged the strikers to remain peaceful with Mitchell traveling to each anthracite town to deliver speeches. Donald Miller and Richard Sharpless write: “Mitchell’s passage through the region took on the aspect of a triumphal march. In Shenandoah [PA], he rode with ‘Big John’ Fahy in an open barouche pulled by black horses … escorted by a guard of honor of well-scrubbed breaker boys and led by a brass band. [See image at the top of this article.] Overhead, stretched across Main Street, was a huge banner: ‘Welcome to Our National Pres., Jno. Mitchell.’ Another banner read, ‘We are slaves now but Mitchell will set us free.'”

Shenandoah, Pennsylvania. A scene in the coal mining town on the occasion of a visit by John Mitchell, labor leader. He is shown riding in a four-horse carriage, the driver of which is wearing a derby hat. Two-horse carriages follow. Above the street is a banner reading “Welcome to our National Pres. Jno. Mitchell” Credit: Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Mounting Pressures and Tensions Around “Scabs”

The coal companies guarded the waste piles even more during the strike. Families sent their children to far away banks to try to avoid standoffs with the coal and iron police. Some miners, under the pressures of starvation from the family’s inability to cook without coal, returned to work. These miners faced the wrath of the community either through the threat of violence or public censure for breaking the strike. The label of “scab” was one that no one wanted.

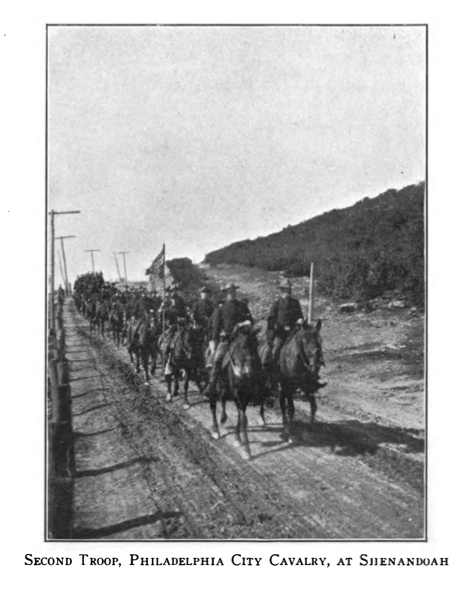

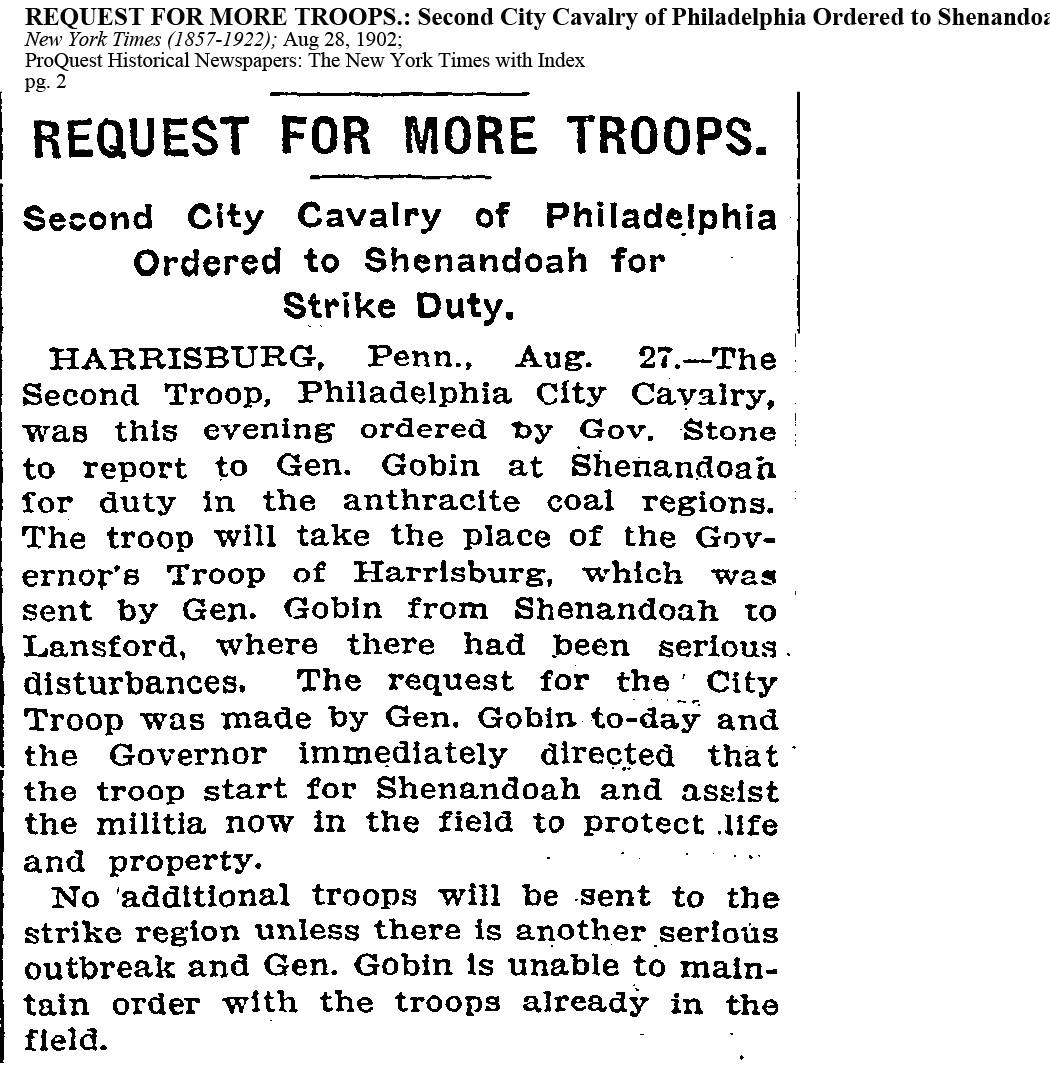

By July 30, 1902 in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, the pressures came to a head when a deputy sheriff was escorting two nonunion men to a breaker and they were attacked by 5,000 strikers. The sheriff took shelter in the Reading Railroad where his brother tried to bring him arms. The strikers beat his brother to death. The sheriff got word out to Governor Stone and subsequently, the town was occupied by Pennsylvania National Guard and Philadelphia City Cavalry troops. The order came from Brigadier General Gobin to shoot to kill and investigate afterwards.

Second Troop Calvary Philadelphia City Cavalry marching into Shenandoah, PA. Credit: A Trooper’s Narrative of Service in the Anthracite Coal Strike, 1902. By Stewart Culin. Published by George W. Jacobs & Company, Philadelphia, PA 1903

Gobin’s entourage didn’t kill anyone, but the presence of the National Guard, along with thousands of coal and iron police—which allegedly included recruits from the lowest members of Philadelphia society—inflamed already existing resentment in the region. These forces were present in addition to at least 1,000 private detectives deployed in the region.

Gobin’s entourage didn’t kill anyone, but the presence of the National Guard, along with thousands of coal and iron police—which allegedly included recruits from the lowest members of Philadelphia society—inflamed already existing resentment in the region. These forces were present in addition to at least 1,000 private detectives deployed in the region.

National Guard encampment at Shenandoah, PA. Credit: Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress

Resolution

By fall, President Theodore Roosevelt formed the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission to investigate the problem and hold hearings representing the first time that the federal government would be involved in labor disputes as a neutral arbitrator. When settled by March 1903, the miners received a 10 percent pay increase, yet the union was not recognized as a bargaining agent.

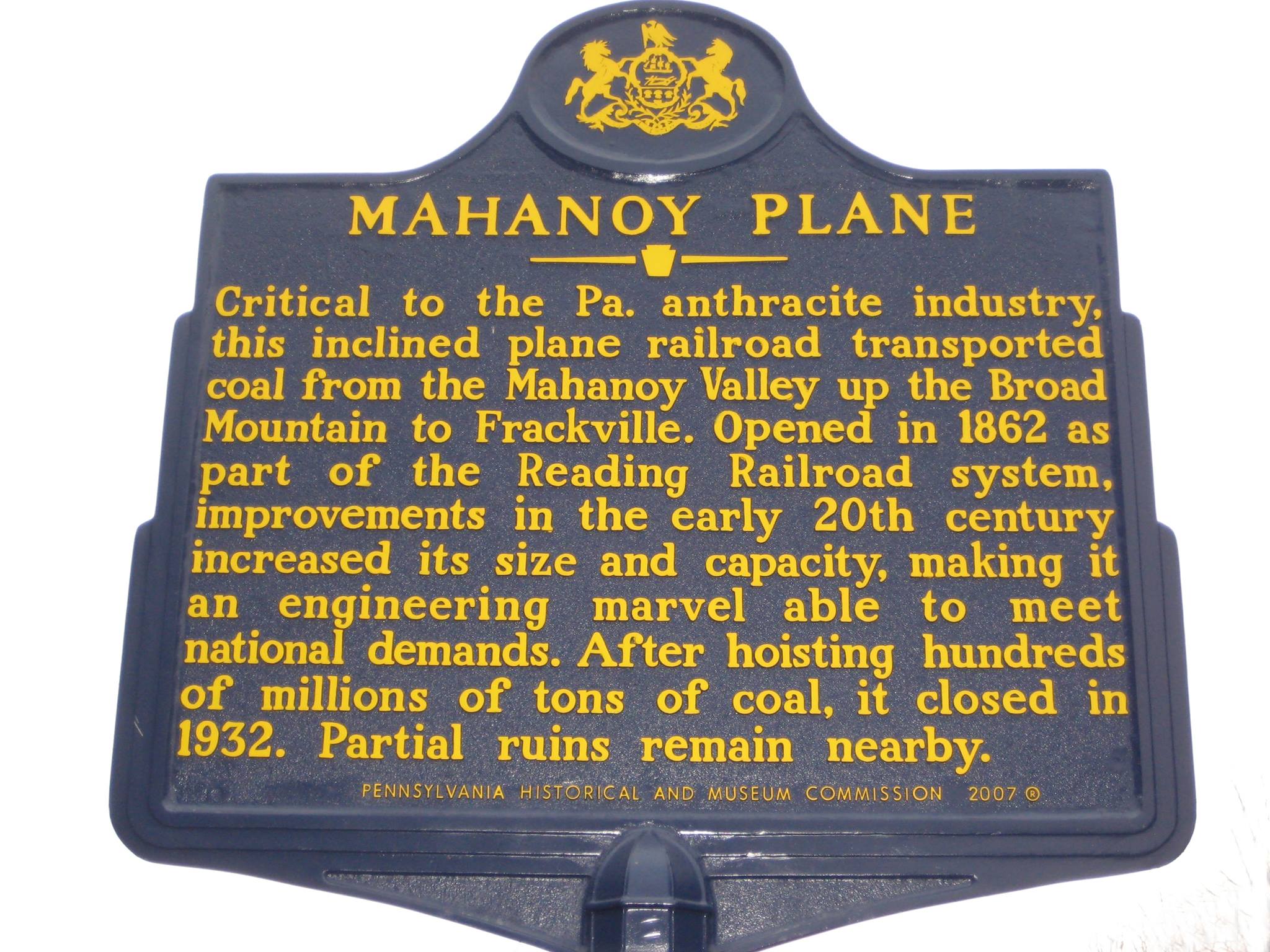

Nowadays, Commonwealth historical markers detailing the strike are dedicated in both Shenandoah and Scranton, Pennsylvania.

References

Dublin, Thomas and Licht, Walter. 2005. The Face of Decline: The Pennsylvania Anthracite Region in the Twentieth Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Miller, Donald L. and Sharpless, Richard E. 1985. The Kingdom of Coal: Work, Enterprise, and Ethnic Communities in the Mine Fields. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.