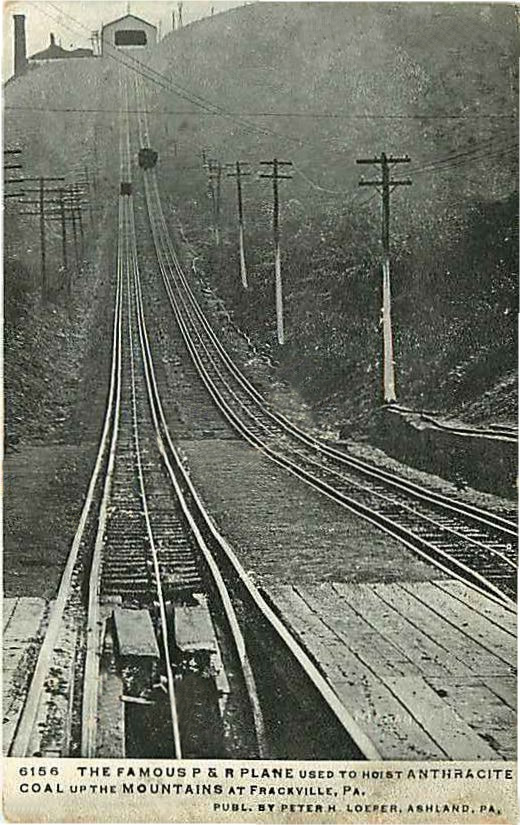

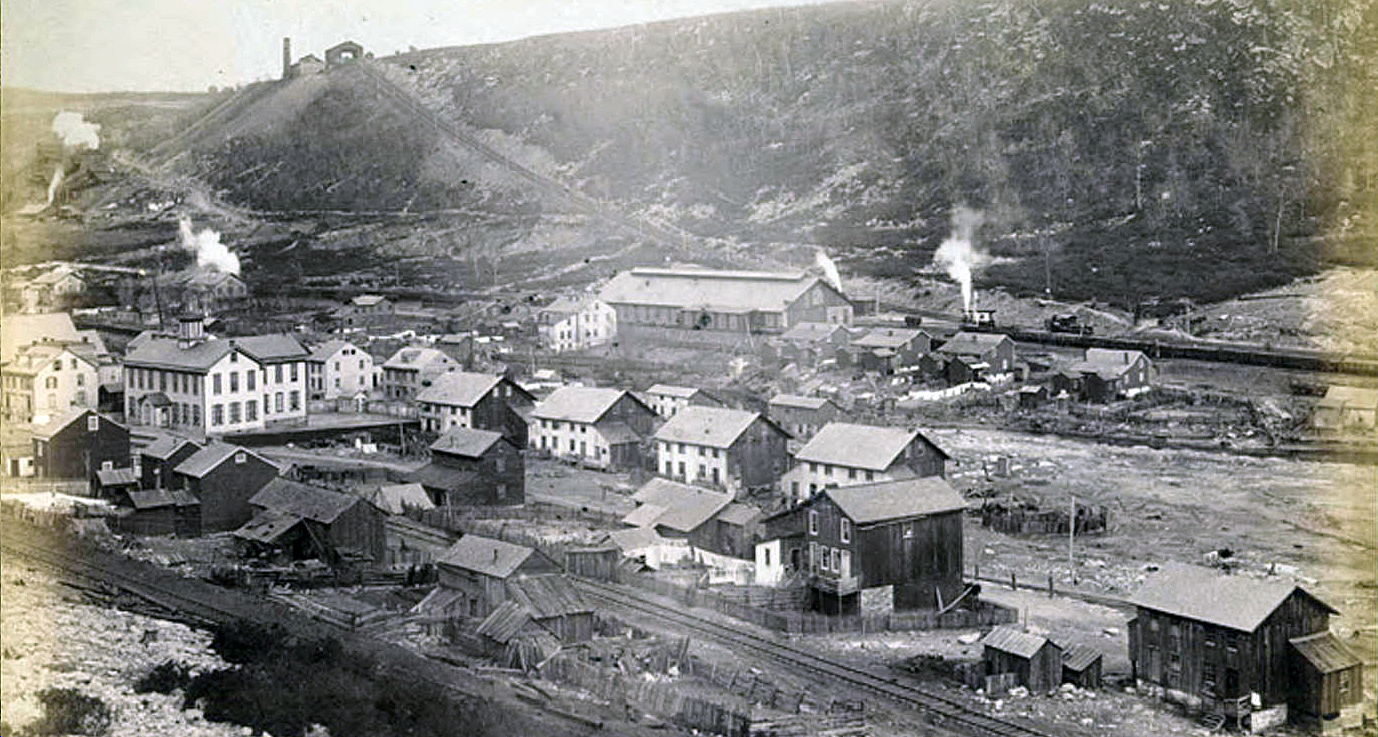

Mahanoy Plane is seen, upper left, atop Broad Mountain. Leading up to it – an angled, yet steep incline – consisting of 2,500 feet of railroad track. Photo from the 1880s.

We’ve written before about Mahanoy Plane and we’ve even done a popular Facebook post.

What makes this post so different? Well, we hope we can give you, our dedicated readers, as much information about engineering of the plane. In a future post, we will be moving onto important people, events, buildings, and so on. For now, we are sharing images and facts about this engineering feat that moved hundreds of millions of tons of anthracite coal up Broad Mountain, just north of Frackville, PA. At the end of this post, we also share a Bray Studios 1920s silent film entitled Black Sunlight showing snippets of the Mahanoy Plane in operation, as well as views of the valley below from the top of the Plane.

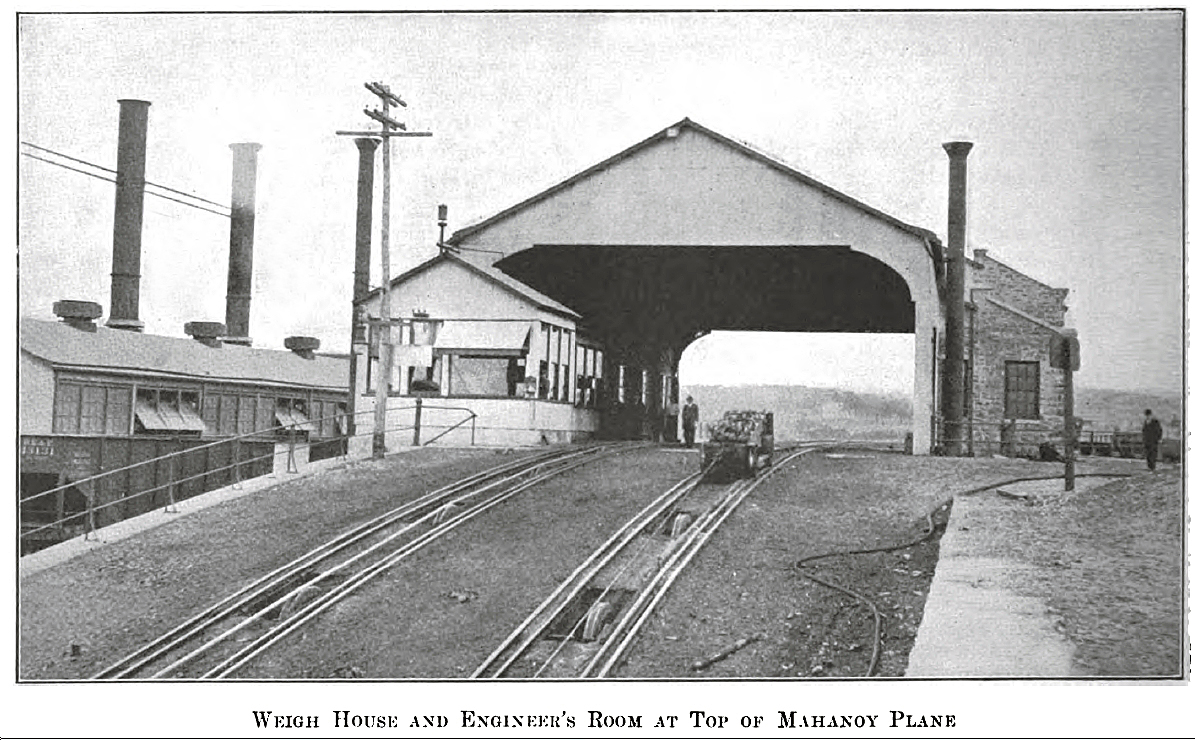

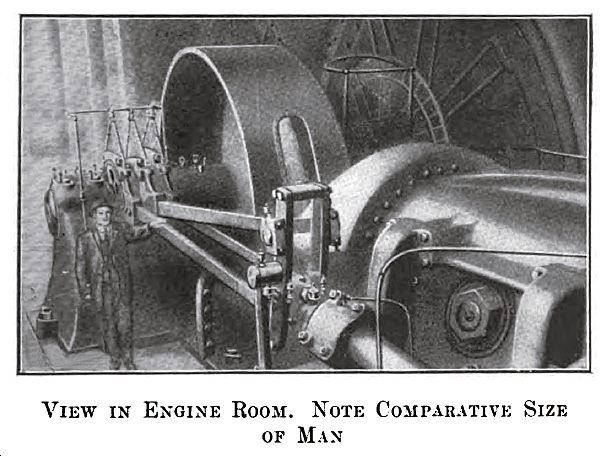

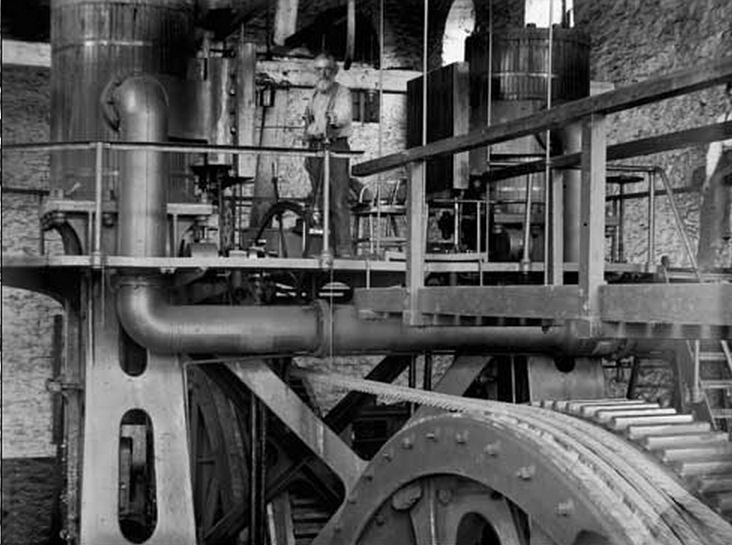

What made this mega-machine run? It was a tandem frictional rope with a 6,000 horsepower steam hoist at Mahanoy Plane as illustrated in the collection of photos below. The anthracite coal from the surrounding 48 collieries went through the plane before it went to market. (48!) To give you an idea of what this volume was like, in January 1913, during 25 working days, (304 hours), the Mahanoy Plane hoisted 19,874 cars of coal.

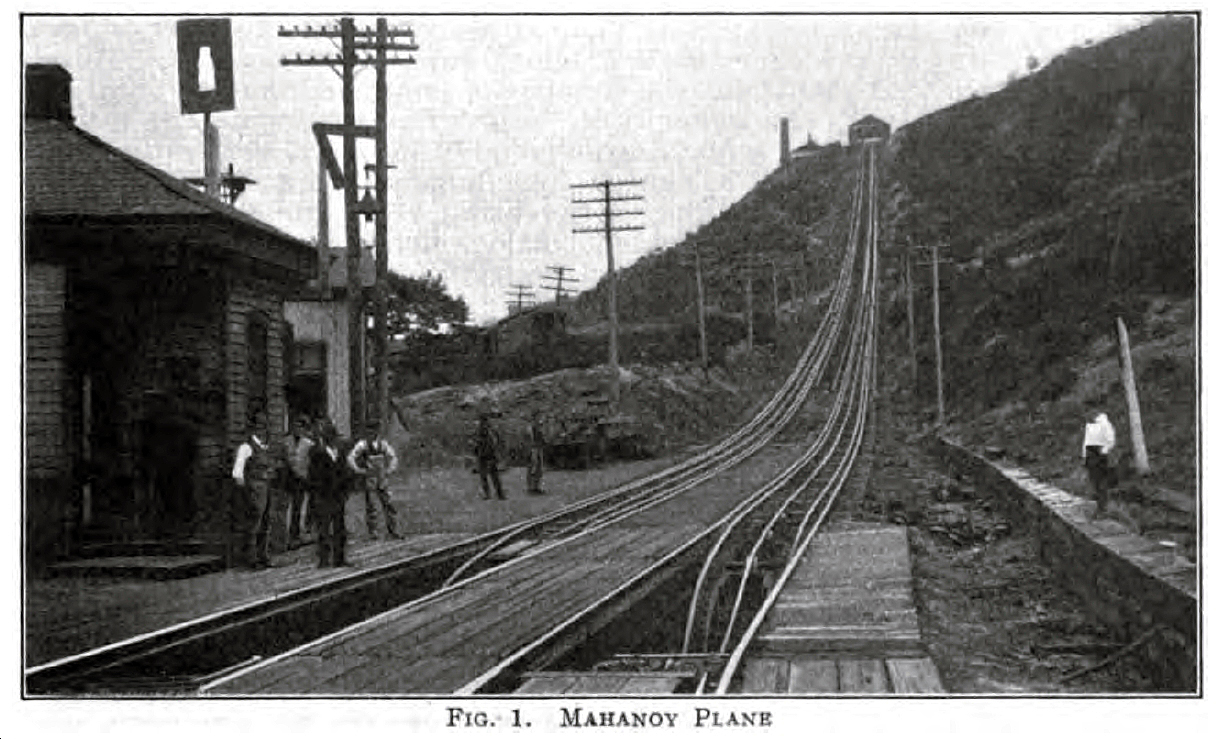

The engine was designed by the superintendent of shops and machinery of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal & Iron Company to hoist an unbalanced load of 190 long tons, up a plane that was 2,500 feet long with an 18% maximum grade and with a piston speed of 600 feet per minute. The bottom of the plane was at an elevation of 1,129 feet above sea level and at the top of the plane was 1,480 feet above sea level – a 351 foot climb.

To operate the plane, 66 men were needed, not including the foreman or the men in the railroad engines to bring the coal to the base or take it away from the top. There were two shifts of 33 men each. When it was running, about 3 3/4 tons of rice-sized coal was needed per hour to supply the steam power.

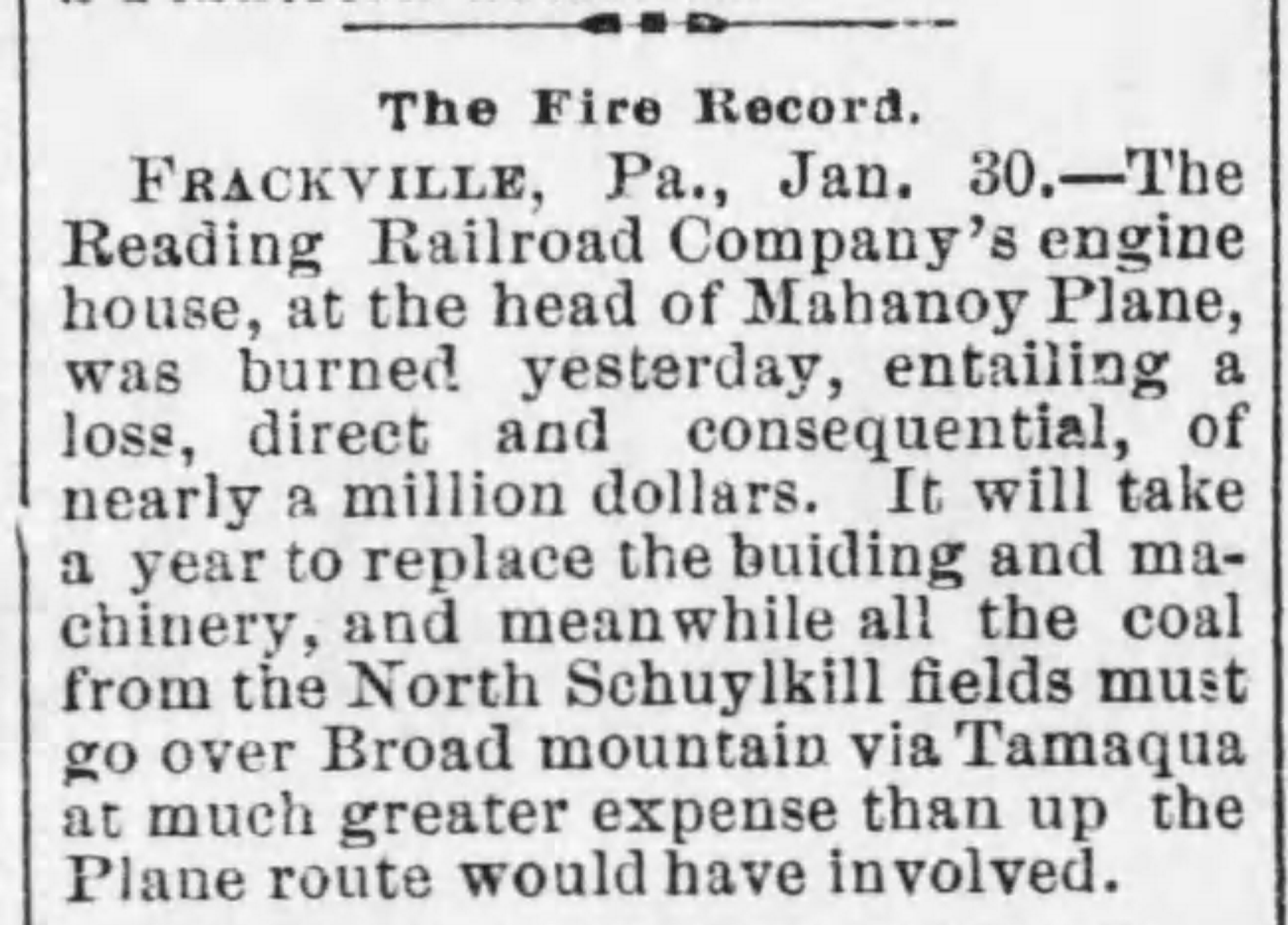

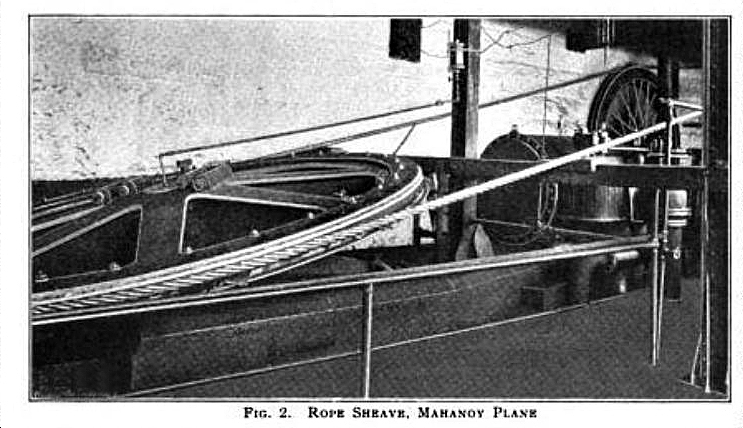

The engine was built by a joint effort of the Reading Iron Company, Scott Foundry Department and the Pottsville Shops of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal & Iron Company. Each of the two engine cylinders was 54 inches in diameter with a 72 inch stroke. The main hoisting rope was 2 and 5/8 inches in diameter and it was made of cast steel, composed of six strands of 19 wires each, around a wire-rope core. At each end of this large cable was a small “barney,” which traveled on a narrower gauge railroad track than the coal cars. When it reached the bottom of the plane, the “barney” passed into a pit under the track. The loaded cars were moved by gravity to a point in front of the “barney” pit. The engine at the top of the mountain was started slowly and the “barney” contacted the rear bumper of the railroad car and it brought the car up the plane. The Mahanoy Plane hoist and engines weighed 500 tons. Despite mechanical breakdowns, rumors of it closing and even an Engine House fire, the plane would operate until 1932.

Below are a series of images, some postcards, and news clippings:

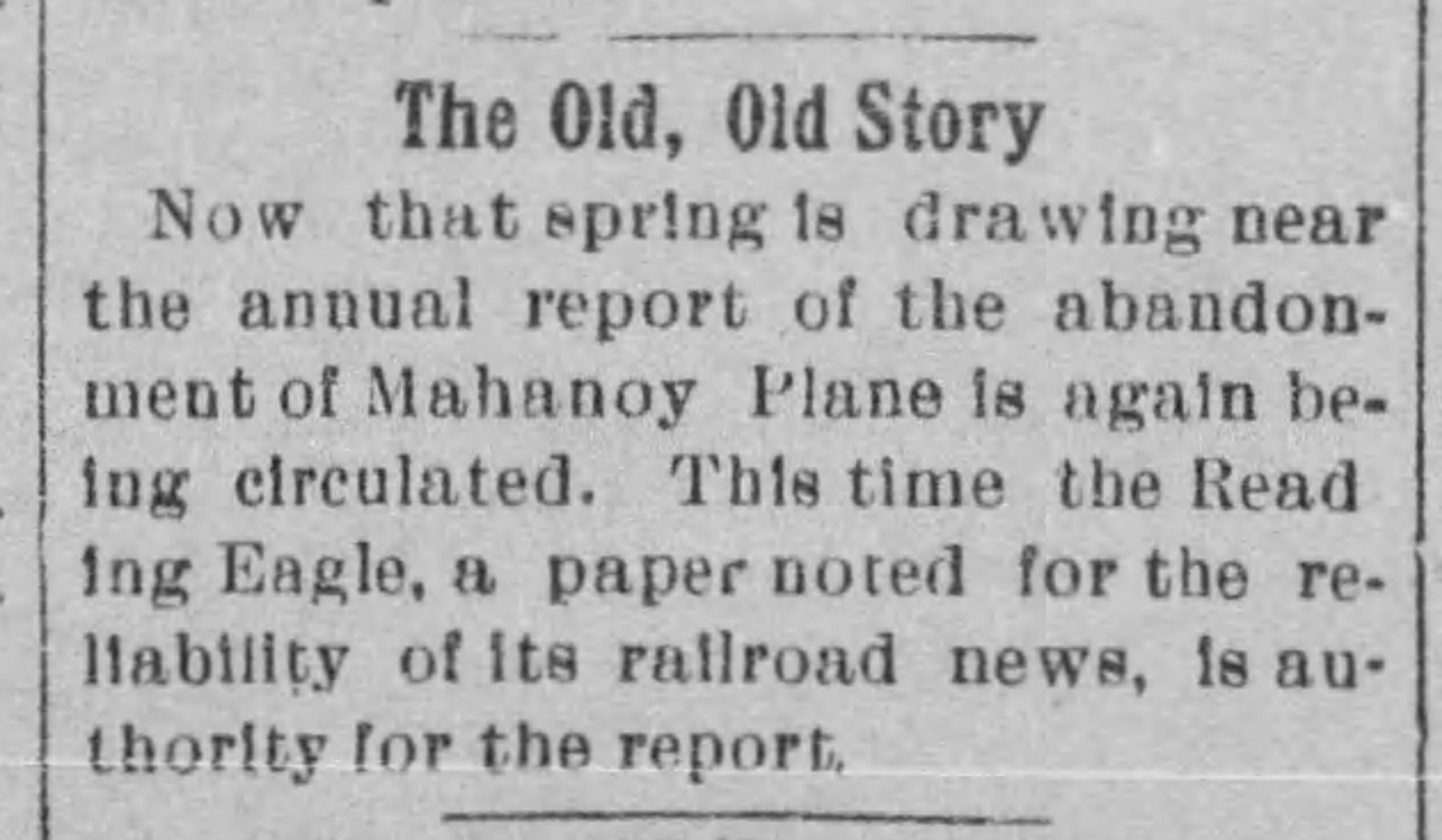

This February 1906 report mentions the “annual” rumor of the Mahanoy Plane shutting down. It remained open until 1932.

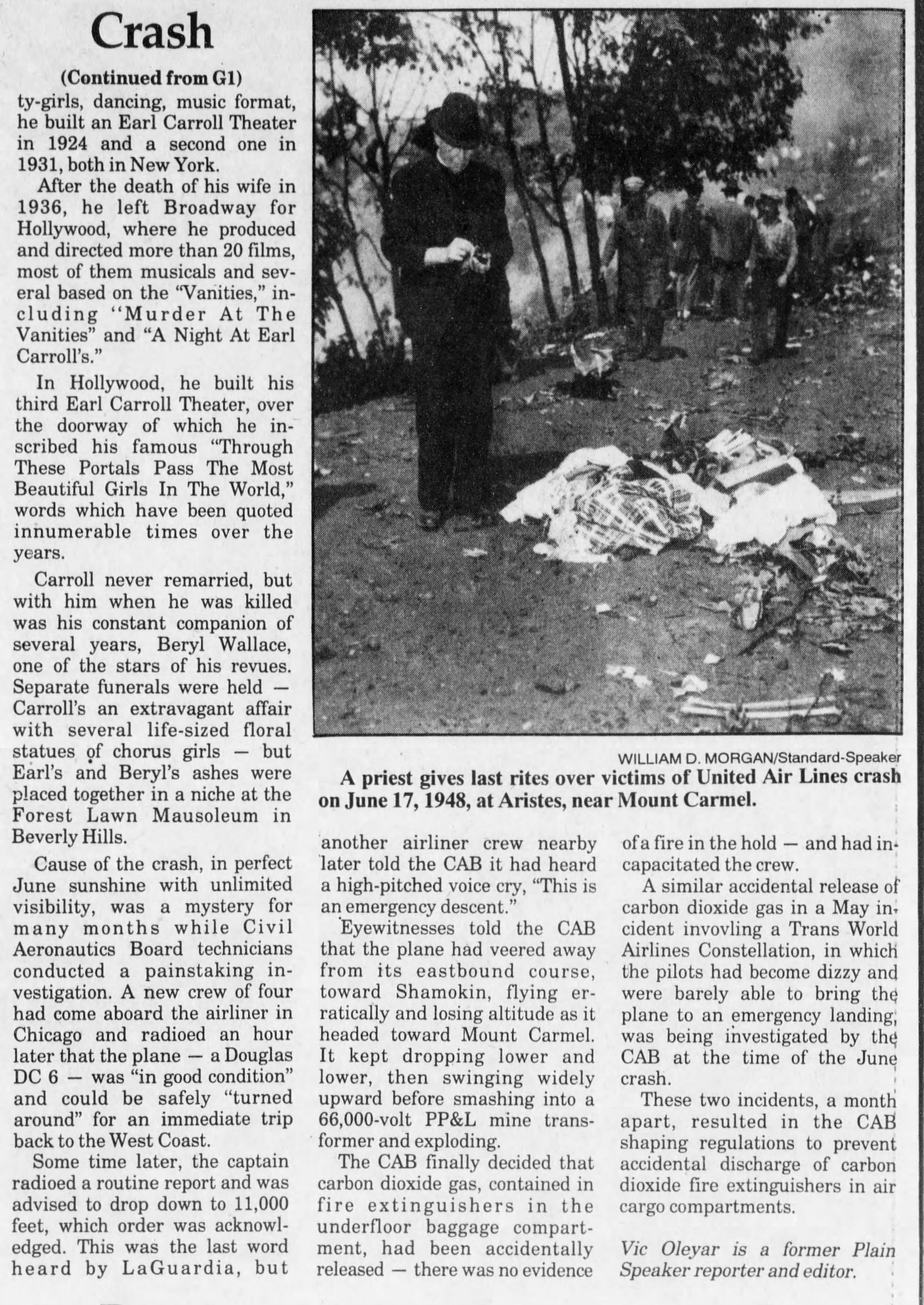

From the 1880s, the Mahanoy Plane in operation, pulling multiple cars of anthracite coal up the incline.

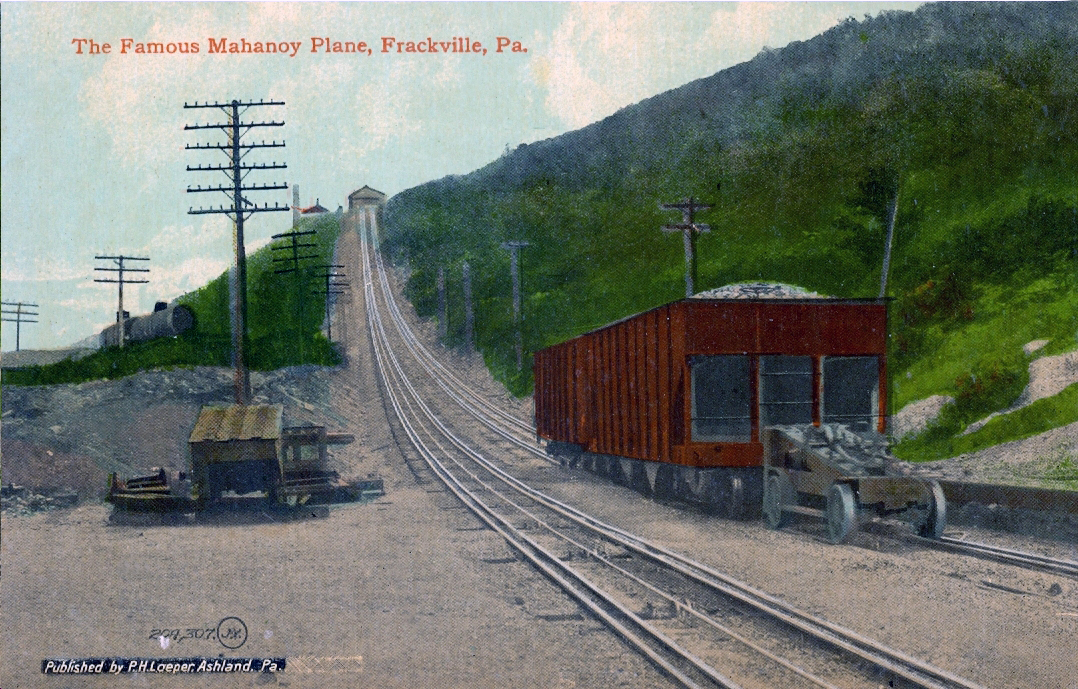

The Mahanoy Plane was a popular topic for picture postcards, and six are reproduced below.

Down below, the small “barney” rides on a narrow gauge track as it pulls the loaded coal car up the incline.

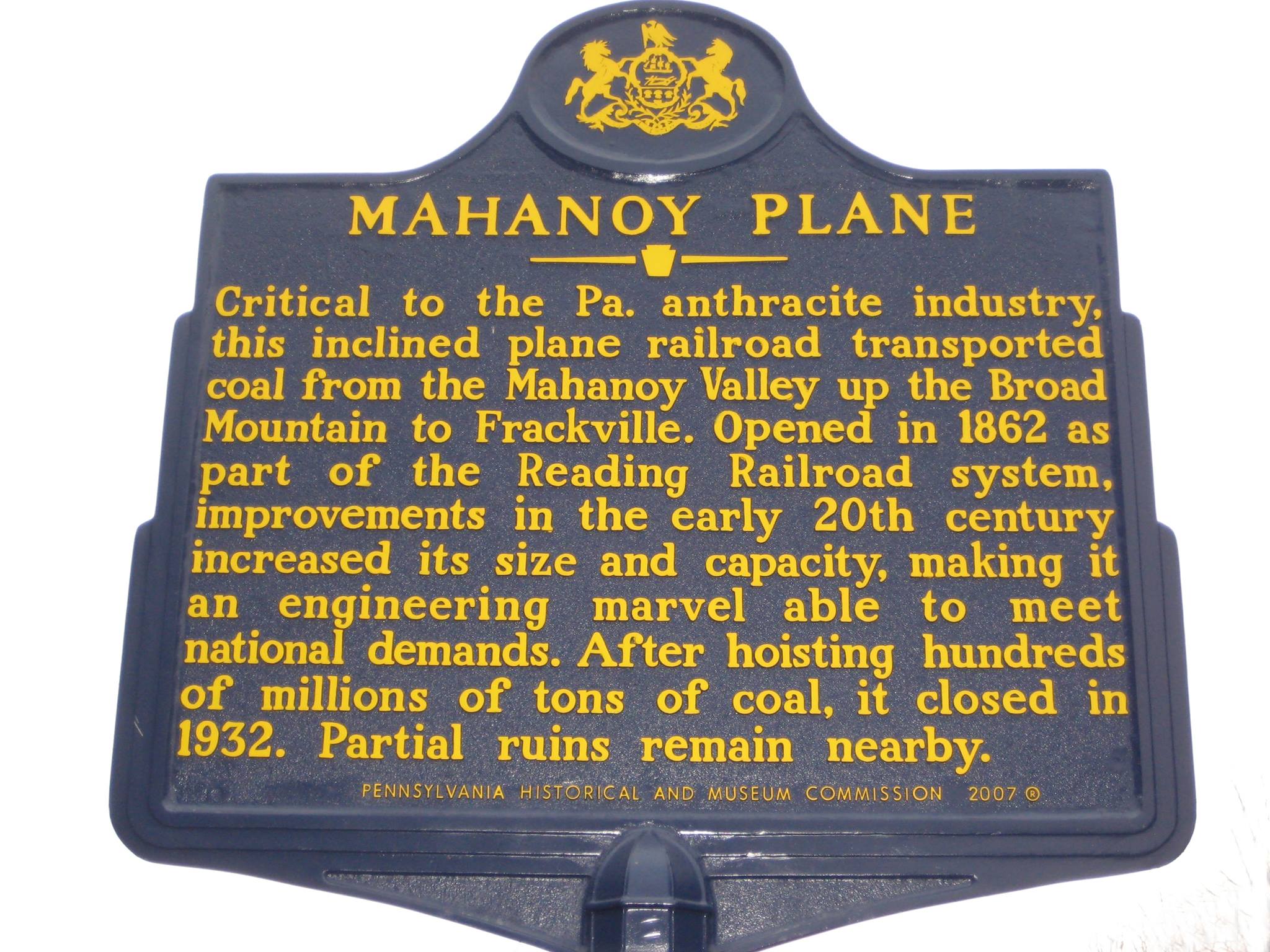

The Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission honored the Mahanoy Plane with a historical marker in 2007.

The 1920’s film Black Sunlight by Bray Studios, contains brief footage of the Mahanoy Plane. The entire video can be viewed at the very end of this article, but these still images show the pertinent scenes:

At the 3:03 mark of the film, there is a sweeping left-to-right view of the valley beneath the Plane, starting at the incline’s railroad tracks:

At 9:47 into the film you are taken for a ride up the plane on a loaded coal car.

At the 10:30 mark, a brief scene at the bottom of the Plane is shown:

Citations:

Kneeland, Frank. A 6,000 Horsepower Steam Hoist. Coal Age. March 1, 1913; Vol. 3, No. 9: 322

Unknown. The Mahanoy Coal Plane. Mines and Minerals October, 1905; Vol. XXVI, No. 3: 101